Young Americans: Behind David Bowie’s Generation-Defining “Plastic Soul” Anthem

Surpassing even its creator’s own expectations, Young Americans was the song that proved David Bowie could master any musical genre he chose.

By Jason Draper

Ever since his first visit to the US, in January 1971, David Bowie had been fascinated with the country. “I focused all my attention on going to America,” he later admitted, adding that he was drawn to what he called the “subculture” of the place: everything from the late Hollywood icon James Dean to rock’n’roll music and Beat Generation writers such as Jack Kerouac and William S Burroughs. Channelling this fixation into an almost stream-of-consciousness narrative in the song ‘Young Americans’, Bowie would seek to express the world view of a new generation of US youth in the same way that he’d waved a flag for the “pretty things” of the UK’s queer underground in the early 70s.

“My Young American was plastic, deliberately so,” Bowie later reflected. “We worked really hard to make that record come alive.” Ushering in a whole new era for Bowie, and leading the charge for a breed of white pop singers with soul music in their hearts, ‘Young Americans’ served notice of the ever-changing star’s most radical reinvention to date.

The backstory: “I was through with theatrical clothes”

Bowie had long drawn upon US culture for his music: avant-garde rock experimentalists The Velvet Underground had informed his Hunky Dory track ‘Queen Bitch’, while the experience of touring The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars across the States in the autumn of 1972 coursed through the wired paranoia of the following year’s Aladdin Sane. Yet it would be the Diamond Dogs Tour of 1974 that set Bowie on the path towards the Young Americans album and its impassioned title track.

A move in this soulful new direction had been clearly signposted. Bowie had opened his revue-styled TV special of 1973, The 1980 Floor Show, with a funk-fuelled new song, ‘1984’, whose frenetic wah-wah guitar sliced through the latter half of the Diamond Dogs album. Now, in the summer of 1974, while touring Diamond Dogs with an ambitious theatrical stage show, he sported sculpted shorn hair and blasted everything from roof-raising Aretha Franklin numbers to the slick dancefloor grooves of the Philadelphia International Records hit machine from his car stereo as he cruised through the States between shows.

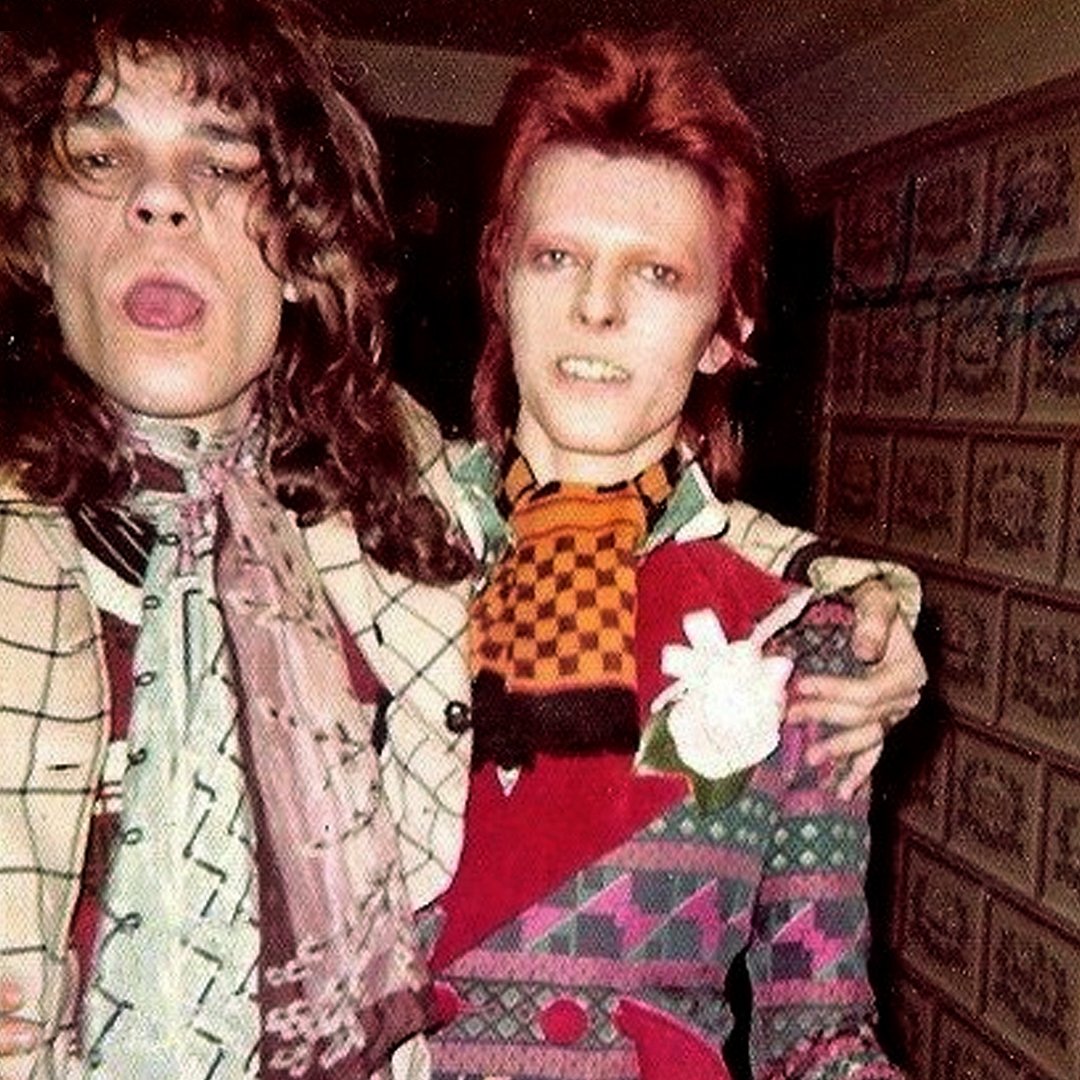

Fitting, then, that his first-ever live album, David Live, would be recorded in Philadelphia. Hitting the shelves that October, it featured an image of Bowie looking every inch the soulful crooner on its sleeve. “I’d got this thing in my mind that I was through with theatrical clothes and I would only wear Sears & Roebuck, which on me looked more outlandish than anything I had made by Japanese designers,” he later told Q magazine, referring to the muted suits he came to favour over the brightly patterned kimonos he’d worn as his Ziggy Stardust alter ago. The Ziggy-era’s songs were also given makeovers, with the dramatic album closer ‘Rock’n’Roll Suicide’ re-emerging as a Southern soul ballad. Soon, Bowie would set up camp in the ‘City of Brotherly Love’, taking over Philadelphia International’s recording base for his next creative leap.

The recording: “That’s a great idea. Put that down”

Booking Sigma Sound Studios, where PIR’s house band, MFSB, had laid down many of the label’s classic cuts, Bowie spent a break between tour legs recording much of what would become his Young Americans album. Having written the album’s title track before entering the studio, Bowie launched straight into it on the first day of the sessions, 11 August 1974. Right behind him was a brand-new band featuring former James Brown sideman Carlos Alomar, whose fluid guitar work would be crucial to Bowie’s seamless switch from rock god to strutting soul boy.

In a move he would repeat 40 years later, when bringing saxophonist Donny McCaslin in to underpin his surprise 2014 single, ‘Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime)’, and, later, the sessions for his final album, ★, Bowie enlisted a hotshot young jazz saxophonist, David Sanborn, to play a style of music outside of his established realm. Setting the scene for Bowie’s tale of wary lovers, Sanborn’s saxophone glistened like a mirror ball. And while the group polished their performance across a week’s worth of sessions, another newcomer listened on from the control booth, ready to put his distinctive stamp on the song.

“What if there was a phrase that went, ‘Young American, young American, he was the young American – all right!” a 23-year-old singer named Luther Vandross, brought to the studio by Alomar, said to Alomar’s wife, Robin Clark. “Now, when ‘all right’ comes up, jump over me and into harmony.” Overhearing the conversation, Bowie told Vandross, “That’s a great idea. Put that down.” Before long, Vandross, Clark and backing singer Ava Cherry were singing Vandross’ parts not only on Young Americans’ title track, but also on most of the album’s songs, among them ‘Fascination’, a number Vandross himself had written under the original title of ‘Funky Music (Is A Part Of Me)’.

The vocals: “A lot of David’s vocals were live because of this wacky idea”

With bass from recent Donny Hathaway and Randy Newman collaborator Willie Weeks, and drums and percussion from Andy Newmark (Sly And The Family Stone, Carly Simon, Rod Stewart) and Larry Washington (MFSB, Salsoul Orchestra), respectively, Bowie ensured that his excursion into blue-eyed soul would cross as easily into the white pop market as he himself had transitioned into the world of Black music. Alongside the newcomers he’d brought in, regular Bowie pianist Mike Garson underpinned the recording with Latin-tinged piano (“I was playing straighter because his music was not was weird as it was in the Aladdin Sane period,” Garson later said) while producer Tony Visconti was back at the helm for his first full project with Bowie since The Man Who Sold The World.

Visconti arrived at Sigma Sound a few days after the Young Americans sessions started. Earlier in the year, he’d helped Bowie mix ‘Rebel Rebel’ for inclusion on Diamond Dogs, but now, jet lagged and severely sleep deprived following a months-long engagement working on Thin Lizzy’s Nightlife album, he was ill-prepared to launch himself into another intensive stint at the controls. Nevertheless, Bowie had his old friend get straight to work solving a technical challenge: how to capture Bowie’s vocals live in the studio while avoiding having his microphone pick up sound from the musicians surrounding him.

“I applied a special technique that was only described to me but I had never used before,” Visconti recalled in the liner notes to the 2016 box set Who Can I Be Now? (1974-1976). “I put up two identical vocal mics, one in front of his mouth and the other in front of his neck. They went through identical channel paths except one was switched out-of-phase on purpose.” Betting that the two microphones would cancel out the sound of the band on the vocal track, Visconti hoped that Bowie’s vocals, picked up by the mic placed in front of his mouth, would come through clearly on the recording. “Damn it, it worked!” Visconti wrote. “A lot of David’s vocals in the final mixes were live because of this wacky idea.”

The lyrics: “It’s about a newly-wed couple who don’t know if they really like each other”

The producer also had an indirect influence on the ‘Young Americans’ lyrics, with Bowie referencing a theatre trip the pair had taken together in the song’s opening line, “They pulled in just behind the fridge.” While many listeners puzzled over why Bowie’s young couple would seek a tryst under cover of a kitchen appliance, the “fridge” in question was actually a nod to Behind The Fridge, a Peter Cook and Dudley Moore show that Bowie and Visconti had been to see in London’s West End the previous year.

The remainder of the song’s lyrical touchstones are, however, undeniably North American. Shifting his focus from the hazardous ghettos of Diamond Dogs’s Hunger City to the metropolises of the United States, Bowie has his references tumble into one another like so much cultural detritus. A Barbie doll, Afro-Sheen hair-care products, the soul-music TV show Soul Train and makes of car (Cadillac, Ford Mustang, Chrysler) all provide the backdrop to – and, perhaps, distraction from – a world in which civilians go about their day under the watchful eye of an intrusive government. “Have you been the un-American?” Bowie asks, referencing the anti-communist House Un-American Activities Committee. “Do you remember your President Nixon?” he probes further, in a lyric written just days after the disgraced commander-in-chief’s resignation.

“It’s about a newly-wed couple who don’t know if they really like each other,” Bowie told NME of the meaning behind ‘Young Americans’. Considering the “predicament” he’d put his couple in – an anti-climactic opening encounter (“It took him minutes, took her nowhere/Heaven knows, she’d have taken anything”) leads to ruminations on ageing and the civil-rights movement – Bowie added, “Well, they do, but they don’t know if they do or don’t.”

No wonder. With ‘Young Americans’ Bowie created a world in which truth and cynicism collide, and emotional fulfilment is scarce. “I heard the news today, oh boy,” Vandross, Clark and Cherry sing at one point, in a canny lift from The Beatles’ ‘A Day in the Life’, although the effect is less a tribute, more resigned acceptance that an era of peace-and-love optimism has long since faded. Turning from his couple, Bowie directly addresses the listener in a near-breathless outpouring that ends with the band dropping out as he makes a final pained entreaty: “Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?”

The release: “Bowie’s most commercial sound to date”

Hysteria of a different type took hold when Bowie invited a small group of fans into Sigma Sound to hear his work-in-progress. Dubbed the ‘Sigma Kids’, this most committed set of devotees had been hanging outside the studio ever since word had spread of Bowie’s presence in the building, and their reaction to the Young Americans material was unequivocal: it spoke directly to the needs of Bowie’s burgeoning US fanbase.

That fanbase gathered to welcome him back to the stage in September, as the Diamond Dogs Tour morphed into The Soul Tour for the remainder of the year. And a nationwide TV audience would be introduced to ‘Young Americans’ when Bowie performed it on The Dick Cavett Show. Filmed on 2 November 1974 and aired on 5 December – more than two months ahead of the song’s release as a single – Bowie’s appearance on the late-night talk show underscored the confidence he had in his new direction. Opening his musical segments with Diamond Dogs’s ‘1984’, he closed the show with a souped-up version of The Flares’ 1961 R&B cut ‘Foot Stomping’, a track which would inspire his John Lennon co-write, ‘Fame’, and followed that with a performance of another Young Americans highlight, ‘Can You Hear Me?’, which was left out of the final broadcast.

All this hard graft on North American soil paid off. Released in a single edit in the US, backed with his David Live version of Eddie Floyd’s Stax Records stormer ‘Knock On Wood’, ‘Young Americans’ would hit No.28 on the Billboard Hot 100, becoming Bowie’s first US hit since a Ziggy-era reissue of ‘Space Oddity’ broke the Top 20. Not that his homeland wasn’t listening. After the full album-length version of ‘Young Americans’ hit UK stores on 21 February, fans took it to No.18 on the charts, the transatlantic success underscoring Record Mirror’s observation that the song boasted “Bowie’s most commercial sound to date”.

The legacy: “It worked in a way I hadn’t really expected”

Half a century on from its release, ‘Young Americans’ barely seems to have aged. Routinely hailed as one of the best David Bowie songs, it has also appeared in Rolling Stone’s ‘500 Greatest Songs of All Time’ list (No.204 in its 2024 update) and Pitchfork’s survey of the 200 best songs of the 70s (No.44). Deeming it the seventh-best Bowie song of all in a Guardian countdown, music critic Alexis Petridis affirmed that “Young Americans represents the point in Bowie’s career where it became apparent he could take virtually any musical genre and bend it to his will”.

Much more genre-bending would follow as the 70s unfolded. But Bowie would return to his “plastic soul” template in 1983, for the world-conquering Let’s Dance album, produced by Chic’s disco architect, Nile Rodgers. Reprised during that era’s Serious Moonlight Tour, ‘Young Americans’ would also get airings throughout the Glass Spider Tour of 1987 and Bowie’s career-spanning Sound+Vision Tour of 1990, before being put to bed for good – to the chagrin of some of his longtime band members, who, in the words of bassist Gail Ann Dorsey, “would just die and go to heaven” for the chance to play the song again.

“It worked in a way I hadn’t really expected,” Bowie would say of his Young Americans era. “It made me a star in America, which is the most ironic, ridiculous part of the equation. Because while my invention was more plastic than anyone else’s, it obviously had some resonance. Plastic soul for anyone who wants it.”

Buy the ‘Young Americans’ 50th-anniversary vinyl reissues and merch at the David Bowie store.